The filmmaker Olga Kosanović was born in Austria, where she has always lived. She only left for vacations and - like many

young Europeans – to study abroad. But when she applied for Austrian citizenship, the authorities calculated that she’d spent

two months too long out of the country. She was stunned to discover that she didn’t belong in the land she had always called

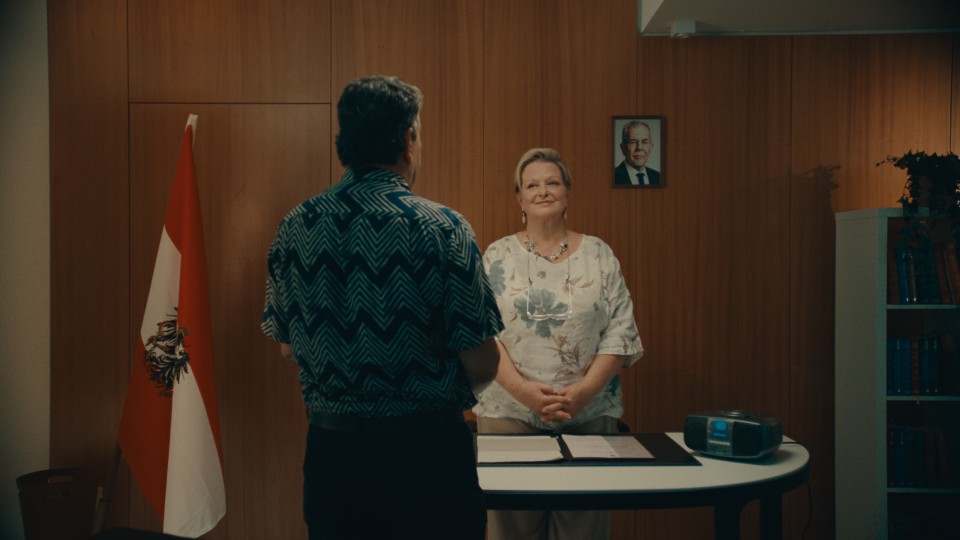

home. Her feature film debut FAR FROM BEING LIPIZZANS records with considerable humour the bureaucratic process of naturalization and reflects on the factual and fictional elements

involved in determining where someone belongs.

You were born in Austria in 1995 – the year that the country joined the EU – and grew up here; three decades later, you have

had to embark on a lengthy process to apply for Austrian citizenship. At what stage in your efforts did your personal story

become the material for a film?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: I was born in Austria and inherited Serbian citizenship from my parents. We had the status of permanent residents, so I grew

up accepting that we had to renew our residence permits every five years. A few years ago, the Austrian NGO SOS Mitmensch (SOS Fellow Citizens) launched a campaign called Born Here, which was intended to make it easier for people born in Austria to acquire citizenship.

When I heard about this, I tried to support the campaign by making a short video explaining what had happened to me, because

my first attempt to obtain Austrian citizenship had been refused, to my complete surprise. The video went viral online for

a short time, it was mentioned in the papers, and there was an article in the left-liberal daily newspaper Der Standard, prompting comments in the Readers’ Forum. I was amazed at the extent to which opinions on the subject differed. One of the

comments was the "Lipizzans remark" which gave me the title of the film, and I found that deeply fascinating as well as upsetting.

Why do so many people immediately adopt such strong views on citizenship?

Can you briefly outline the stages and timeframe of the naturalization process?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: Right now, I’m going through this process for the second time. It begins with a mandatory initial information event. Then

you start working through the list of required documents. When you’ve got about half of them, you’re advised to register for

an appointment: the waiting period is at least a year. This appointment is only the date when you submit all the documents

– and then the authorities start working through them. After a few months, you are told which documents are missing, you submit

more, and then you wait again. I've been waiting for seven months now, and I don't know where I stand. I was born in Austria

and graduated from high school here; people who don’t fulfill those criteria also need to obtain a certificate of German language

proficiency and pass a naturalization test.

How many people live in Vienna / Austria without Austrian citizenship? What are the consequences for them in terms of the

right to vote?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: As of autumn 2024, 19.2% of people with a registered place of residence in Austria did not have Austrian citizenship and

were therefore not entitled to vote. In Vienna, around 35% of registered residents are not eligible to vote, and that figure

is rising.

Did the fact that Austrian law does not regard you as Austrian trigger your reflections about the sense of togetherness and

being different?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: I had a lovely, sheltered childhood in Vienna. I never had the feeling that I didn't belong, except for a few moments when

you’re standing at a border and your passport is a different colour than your best friends’. I walked into the office to apply

for Austrian citizenship feeling: OK, so now I'll get official confirmation of the status I've had for the last thirty years anyway. When the official said: "First we’ll have to see whether you’re even suitable for integration," I was absolutely stunned.

Only then was I confronted by the frightening realization that I’d grown up in a place where there’s an "us" and a "them"

– and suddenly I didn't belong to the "us".

You employ a very inventive film concept, with fictional and documentary elements. Let’s talk first about the fictional ones.

They include games that you have come up with. Why did you want the principle of play and chance to set the initial cinematic

tone?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: When I told people I was working on a film about citizenship, they would usually snort, their first associations being something

like: dry topic, not cinematic, bland, bureaucratic. So my challenge was how to present this really dry subject, to make it

as accessible as possible, ideally in such a way that it would move the audience from one element to the next while keeping

them captivated. I also felt it was important that the audience shouldn’t be allowed to sit back and think: Yeah, but that doesn't affect me.

Robert Menasse says in an interview: A homeland is a human right, while a nation is a fiction. Does the formal mixture of fictional and documentary elements in the film also reflect the hybrid nature of the theme? After

all, there’s a brutal reality to being or not being a citizen of a country, but awarding citizenship has an indefinable and

very emotional component.

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: Yes, that's a good way to put it. It is also an invented principle which everyone builds their reality on. It's exciting

to break that down and bring another way of thinking to play. This fiction is a permanent reality that at some point determines

our everyday lives. I think Robert Menasse's quote is great, because the term homeland is so often used in a different way and has been corrupted in politics. Everyone wants the feeling of having a homeland. But that has nothing to do with the nation, which only pretends to be the place that supplies a sense of homeland.

The offensive quote from the Internet forum which you adopt for your title is: If a cat has kittens in in the Riding School, they’re far from being Lipizzans. It also prompted you to investigate the supposedly Austrian national symbol of the Lipizzan horse. What did you find out?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: That they’re far from being as Austrian as they’re claimed to be. It is a very traditional symbol that’s widely employed.

Here, too, I found it interesting to break down the fiction behind it. The film also tries to deconstruct this comment from

the forum, but at the same time it interests me, because it seems to epitomize the fiction so many people believe: We are thoroughbred Lipizzans, they are cats. For me, it was also important to maintain a light touch about these things. I can perceive this comment as a racist

insult or arm myself with humor, take the sentence apart and write a response.

You capture the stages of the naturalization process in documentary style. What particularly stands out for you, looking back?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: It was very important to us that the film should also reflect the documentary harshness of the reality. That's why the documentary

moments are there. One good example is the initial information event. The great thing for us as a film team was the opportunity

to see all those faces, those different individuals, and appreciate the huge number of people who are interested in Austrian

citizenship for a wide range of reasons. At the end of the event, there’s an opportunity for people to put individual questions.

And the interesting thing was that nobody left. Everybody had a question. Every case is so different. Which also demonstrates

the complexity, the impossibility of dealing with every individual history by means of one law.

In addition to experts, you also talk to people in an abstract setting, encompassing various generations and ethnicities,

people who represent society in all its diversity. What was important to you about these discussions?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: We wanted to hear people’s frank opinions as distinct from expert statements, and to have conversations in focused settings.

We invited people I knew about, whose applications were being processed or had already been rejected, but in addition to that,

we simply stopped people on the street and asked if they could spare us 15 minutes. A great many of them were willing to do

so. And then we went to places frequented by people who aren't in our bubble. We had great conversations with everyone. I

tried to remain as open as possible to whatever emerged. I wanted to capture a wide range of views. Hopefully, the conclusion

that emerges represents what migration researcher Judith Kohlenberger calls the growing pains of the we. People with diverse views have to meet and listen to each other. That's what we tried to do.

You also address the subject of dual citizenship and the fact that applying for Austrian citizenship entails giving up your

original citizenship. You yourself become aware of the difficulty involved here in the end.

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: It was an interesting process. In the past, I would have said: I don't care, I have much less in common with Serbia than with Austria. Looking back, I don't think I would have dared to say that Serbian citizenship was important to me. I’d have been afraid that

saying that would weaken my credibility, my affiliation with Austria. It was probably a defense mechanism, too. In the debate

about citizenship and belonging, there is always only room for one or the other. In purely factual terms, though, our society

doesn’t function that way; for a long time it has been far more pluralistic than the discussion would like to admit. Judith

Kohlenberger says: Allowing dual citizenship would be a sign of the acceptance of diversity, as it has long prevailed. I am fluent in Serbian; my family’s from that country. Why do I have to negate one to prove the other? Dual citizenship would

be the only right thing for me. If I have to choose, Austrian citizenship is more obvious. So at some point I will give up

Serbian citizenship.

You often hear people say that they end up not feeling they belong anywhere. Do you feel the only solution is with multiple

citizenship?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: That's how I see it. But it’s only possible if Austria, as the country that accepts you, says: Where you come from is a part of you, and at the same time you are one of us. Unfortunately, we’re still very far from that point in political terms. But young people today seem to have a much cooler

and more self-confident approach, which is a good development that makes me a bit optimistic.

Interview: Karin Schiefer

January 2025

FAR FROM BEING LIPIZZANS

Olga Kosanović

There’s an "us" and a "them"

Quote: Why do so many people immediately adopt such strong views on citizenship?

The filmmaker Olga Kosanović was born in Austria, where she has always lived. She only left for vacations and - like many

young Europeans – to study abroad. But when she applied for Austrian citizenship, the authorities calculated that she’d spent

two months too long out of the country. She was stunned to discover that she didn’t belong in the land she had always called

home. Her feature film debut FAR FROM BEING LIPIZZANS records with considerable humour the bureaucratic process of naturalization

and reflects on the factual and fictional elements involved in determining where someone belongs.

You were born in Austria in 1995 – the year that the country joined the EU – and grew up here; three decades later, you have

had to embark on a lengthy process to apply for Austrian citizenship. At what stage in your efforts did your personal story

become the material for a film?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: I was born in Austria and inherited Serbian citizenship from my parents. We had the status of permanent residents,

so I grew up accepting that we had to renew our residence permits every five years. A few years ago, the Austrian NGO SOS

Mitmensch (SOS Fellow Citizens) launched a campaign called Born Here, which was intended to make it easier for people born

in Austria to acquire citizenship. When I heard about this, I tried to support the campaign by making a short video explaining

what had happened to me, because my first attempt to obtain Austrian citizenship had been refused, to my complete surprise.

The video went viral online for a short time, it was mentioned in the papers, and there was an article in the left-liberal

daily newspaper Der Standard, prompting comments in the Readers’ Forum. I was amazed at the extent to which opinions on the

subject differed. One of the comments was the "Lipizzans remark" which gave me the title of the film, and I found that deeply

fascinating as well as upsetting. Why do so many people immediately adopt such strong views on citizenship?

Can you briefly outline the stages and timeframe of the naturalization process?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: Right now, I’m going through this process for the second time. It begins with a mandatory initial information

event. Then you start working through the list of required documents. When you’ve got about half of them, you’re advised to

register for an appointment: the waiting period is at least a year. This appointment is only the date when you submit all

the documents – and then the authorities start working through them. After a few months, you are told which documents are

missing, you submit more, and then you wait again. I've been waiting for seven months now, and I don't know where I stand.

I was born in Austria and graduated from high school here; people who don’t fulfill those criteria also need to obtain a certificate

of German language proficiency and pass a naturalization test.

How many people live in Vienna / Austria without Austrian citizenship? What are the consequences for them in terms of the

right to vote?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: As of autumn 2024, 19.2% of people with a registered place of residence in Austria did not have Austrian citizenship

and were therefore not entitled to vote. In Vienna, around 35% of registered residents are not eligible to vote, and that

figure is rising.

Did the fact that Austrian law does not regard you as Austrian trigger your reflections about the sense of togetherness and

being different?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: I had a lovely, sheltered childhood in Vienna. I never had the feeling that I didn't belong, except for a

few moments when you’re standing at a border and your passport is a different colour than your best friends’. I walked into

the office to apply for Austrian citizenship feeling: OK, so now I'll get official confirmation of the status I've had for

the last thirty years anyway. When the official said: "First we’ll have to see whether you’re even suitable for integration,"

I was absolutely stunned. Only then was I confronted by the frightening realization that I’d grown up in a place where there’s

an "us" and a "them" – and suddenly I didn't belong to the "us".

You employ a very inventive film concept, with fictional and documentary elements. Let’s talk first about the fictional ones.

They include games that you have come up with. Why did you want the principle of play and chance to set the initial cinematic

tone?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: When I told people I was working on a film about citizenship, they would usually snort, their first associations

being something like: dry topic, not cinematic, bland, bureaucratic. So my challenge was how to present this really dry subject,

to make it as accessible as possible, ideally in such a way that it would move the audience from one element to the next while

keeping them captivated. I also felt it was important that the audience shouldn’t be allowed to sit back and think: "Yeah,

but that doesn't affect me".

Robert Menasse says in an interview: A homeland is a human right, while a nation is a fiction. Does the formal mixture of

fictional and documentary elements in the film also reflect the hybrid nature of the theme? After all, there’s a brutal reality

to being or not being a citizen of a country, but awarding citizenship has an indefinable and very emotional component.

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: Yes, that's a good way to put it. It is also an invented principle which everyone builds their reality on.

It's exciting to break that down and bring another way of thinking to play. This fiction is a permanent reality that at some

point determines our everyday lives. I think Robert Menasse's quote is great, because the term homeland is so often used in

a different way and has been corrupted in politics. Everyone wants the feeling of having a homeland. But that has nothing

to do with the nation, which only pretends to be the place that supplies a sense of homeland.

The offensive quote from the Internet forum which you adopt for your title is: If a cat has kittens in in the Riding School,

they’re far from being Lipizzans. It also prompted you to investigate the supposedly Austrian national symbol of the Lipizzan

horse. What did you find out?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: That they’re far from being as Austrian as they’re claimed to be. It is a very traditional symbol that’s widely

employed. Here, too, I found it interesting to break down the fiction behind it. The film also tries to deconstruct this comment

from the forum, but at the same time it interests me, because it seems to epitomize the fiction so many people believe: We

are thoroughbred Lipizzans, they are cats. For me, it was also important to maintain a light touch about these things. I can

perceive this comment as a racist insult or arm myself with humor, take the sentence apart and write a response.

You capture the stages of the naturalization process in documentary style. What particularly stands out for you, looking back?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: It was very important to us that the film should also reflect the documentary harshness of the reality. That's

why the documentary moments are there. One good example is the initial information event. The great thing for us as a film

team was the opportunity to see all those faces, those different individuals, and appreciate the huge number of people who

are interested in Austrian citizenship for a wide range of reasons. At the end of the event, there’s an opportunity for people

to put individual questions. And the interesting thing was that nobody left. Everybody had a question. Every case is so different.

Which also demonstrates the complexity, the impossibility of dealing with every individual history by means of one law.

In addition to experts, you also talk to people in an abstract setting, encompassing various generations and ethnicities,

people who represent society in all its diversity. What was important to you about these discussions?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: We wanted to hear people’s frank opinions as distinct from expert statements, and to have conversations in

focused settings. We invited people I knew about, whose applications were being processed or had already been rejected, but

in addition to that, we simply stopped people on the street and asked if they could spare us 15 minutes. A great many of them

were willing to do so. And then we went to places frequented by people who aren't in our bubble. We had great conversations

with everyone. I tried to remain as open as possible to whatever emerged. I wanted to capture a wide range of views. Hopefully,

the conclusion that emerges represents what migration researcher Judith Kohlenberger calls the growing pains of the we. People

with diverse views have to meet and listen to each other. That's what we tried to do.

You also address the subject of dual citizenship and the fact that applying for Austrian citizenship entails giving up your

original citizenship. You yourself become aware of the difficulty involved here in the end.

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: It was an interesting process. In the past, I would have said: I don't care, I have much less in common with

Serbia than with Austria. Looking back, I don't think I would have dared to say that Serbian citizenship was important to

me. I’d have been afraid that saying that would weaken my credibility, my affiliation with Austria. It was probably a defense

mechanism, too. In the debate about citizenship and belonging, there is always only room for one or the other. In purely factual

terms, though, our society doesn’t function that way; for a long time it has been far more pluralistic than the discussion

would like to admit. Judith Kohlenberger says: Allowing dual citizenship would be a sign of the acceptance of diversity, as

it has long prevailed. I am fluent in Serbian; my family’s from that country. Why do I have to negate one to prove the other?

Dual citizenship would be the only right thing for me. If I have to choose, Austrian citizenship is more obvious. So at some

point I will give up Serbian citizenship.

You often hear people say that they end up not feeling they belong anywhere. Do you feel the only solution is with multiple

citizenship?

OLGA KOSANOVIĆ: That's how I see it. But it’s only possible if Austria, as the country that accepts you, says: Where you come

from is a part of you, and at the same time you are one of us. Unfortunately, we’re still very far from that point in political

terms. But young people today seem to have a much cooler and more self-confident approach, which is a good development that

makes me a bit optimistic.