As a student in the 1970s, Nathalie Borgers' husband Abidin was involved in the flourishing Turkish democracy movement – and

also experienced its suppression. Scars on his body still bear witnesses to a personal and political turning point. The military

coup in 1980 forced him to make a new start in Vienna, which gave rise to a break with the past while also forging an unbroken

connection. In SCARS OF A PUTSCH, the filmmaker tries to get to the bottom of the mystery that Abidin contains within himself by tracing a movement of social

awakening and the powerful forces opposing it.

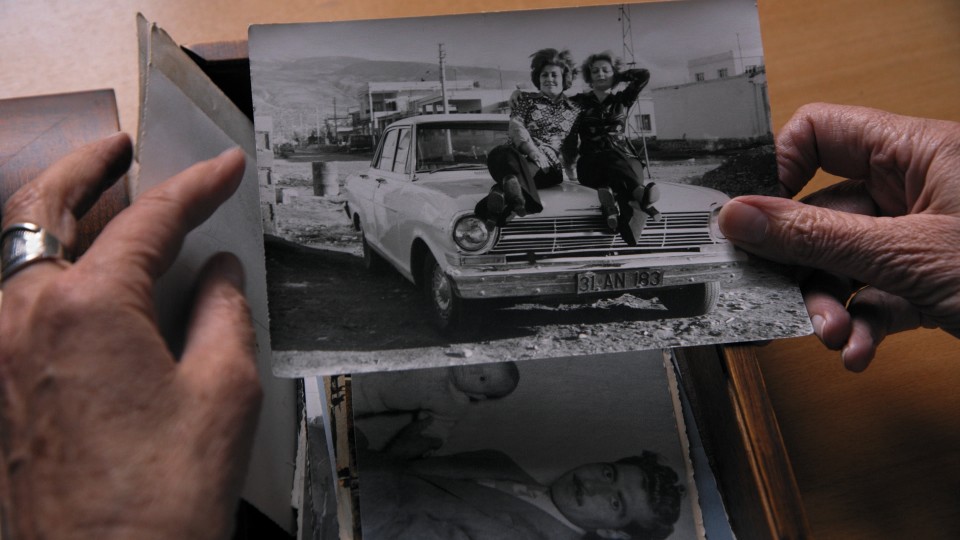

You start the film with a close-up of your husband's upper body. The camera, which refocuses time and again, searches for

scars that are barely visible but conceal within them the history of a man and an entire country. Were these scars a taboo

which prompted you to set off in search of the explanations behind them?

NATHALIE BORGERS: There wasn’t a taboo. Abidin told me about it when we first met. He personally put these events behind him long ago. And I

must say I was very happy to meet a man who existed completely in the present and was content with his life. I'm ten years

younger than him, and as a 16-year-old in Belgium I’d heard virtually nothing about the military coup in Turkey. In any case,

we haven’t based our relationship on these political experiences. In 2008/2010, Turkey was in turmoil. Abidin said at the

time that political Islam and democracy were completely incompatible. I have gradually appreciated from his analyses, that

his assessment of the political situation in his country was correct from a long perspective. When we were confined to the

apartment during Covid, he was obsessed with following the Turkish news. The idea grew within me that I didn't really know

my husband, and I began to ask questions: Where do these scars come from? What shapes his relationship with Turkey?

Your husband Abidin came to Vienna in January 1981. Can you describe the political background that forced him to leave his

home and his family?

NATHALIE BORGERS: Abidin was born in 1954 and began studying at the Middle-Eastern Technical University in Ankara in the early seventies. At

that time, it was a stronghold for left-wing and democratic modes of thought. Abidin's university was a particularly active

campus. The movement grew stronger and stronger, but from 1975 fascist militias began to appear on the scene, intent on dismantling

it step by step. These efforts were supported by the far-right party, which had come to power in a coalition. Representatives

of the left-wing movement were shot in the street, people were blackmailed, there were serious bomb incidents which were then

blamed on the left. Abidin was wounded by gunfire in 1976. Some sectors of the movement then armed themselves, and a kind

of civil war developed on the streets. The military coup didn’t take place until 1980, officially to put an end to the civil

war. Between 1975 and 1980, however, the attacks of the Grey Wolves on the Left were already preparing the ground for that.

In previous years the IMF had called for neoliberal measures, which were successfully resisted for a while by the left-wing

movement.

Why did Abidin leave Turkey?

NATHALIE BORGERS: After the coup of September 12, 1980, left-wing political activists had two options: they could either stay and end up in

prison, or flee. Abidin knew that if he was caught, there would be no mercy for him; even though he had never been on the

front line, he would be imprisoned and tortured. He immediately went into hiding, but he couldn't expect friends and family

to hide him in the long run. It was clear that he had to leave. A few months after the coup – just as the Christmas holidays

came to an end – he came to Vienna on a guest worker bus.

As well as depicting the consequences of his gunshot wounds, the film also reveals the scars that political developments have

left in his family, in his immediate environment and in society. Did you expect this personal story would lead you to such

a far-reaching examination of the topic?

NATHALIE BORGERS: The overall social context was very important to me, because I wanted to make it clear that the foundation for the present

political situation was laid at that time, when neoliberalism was coupled with a military regime that brought religion into

the equation and fostered those two forces in parallel. On another level, I would have liked to explore Abidin's story more,

but I couldn't involve many of his family members without putting them in danger. Some couldn’t talk at all, while others

only wanted to talk about certain topics. During the period when I was developing the film, the situation became more complicated.

Simply travelling to some of the places would have been too dangerous. So I had to find a wider spectrum of people to talk

to, including some people Abidin didn’t know.

Did you become conscious of a discrepancy between your knowledge about the country, rooted in your private connection, and

the image formed by external media perceptions?

NATHALIE BORGERS: I came to realize yet again how little we know about politics in other countries. Including me. We have a particular way of

thinking, and everything is filtered through it. That keeps us from looking at things from a different perspective. Turkey

has a very complicated history. A lot of people don’t appreciate the conditions there. We even had someone in our team who

was really surprised that Turkish people could have a modern worldview or wear shirts and sweaters. In SCARS OF A PUTSCH,

I wanted to go back and trace the origins of political change. But of course, as a result of talking to Abidin and our Turkish

friends, I had a different kind of understanding than the general public here. Simply because I had to ask a lot of questions

again and again.

You also portray very moving encounters with women: your sister-in-law Kıvanç, Perihan, the mother of Cahit, an activist who

spent eight years in prison, and Yeter Güneş, who escaped the death penalty as a very young woman. What did you find particularly

impressive?

NATHALIE BORGERS: The women impressed me a lot. My sister-in-law Kıvanç, and Yeter, are the same age as me, so they were 16 at the time of

the putsch, and in the years before that Yeter had been very committed and played a role in the movement, though a small one.

What impressed me very much about the women was their personal devotion to social justice and, above all, to gender equality.

In conversations with my sister-in-law, I discovered some very fine things about my husband. He loved his "little" sister

very much and did a great deal to support her, as the youngest in the family. It was touching to learn how he took care of

her, and to see how women supported their sons: Cahit's mother, for example, shared her sons’ political ideas even though

she was afraid that they might lose their lives for a political struggle. She persevered and always thought it was important.

During the course of your work, did you sense in this generation of activists a desire for amends to be made, or at least

for history to do justice to those times?

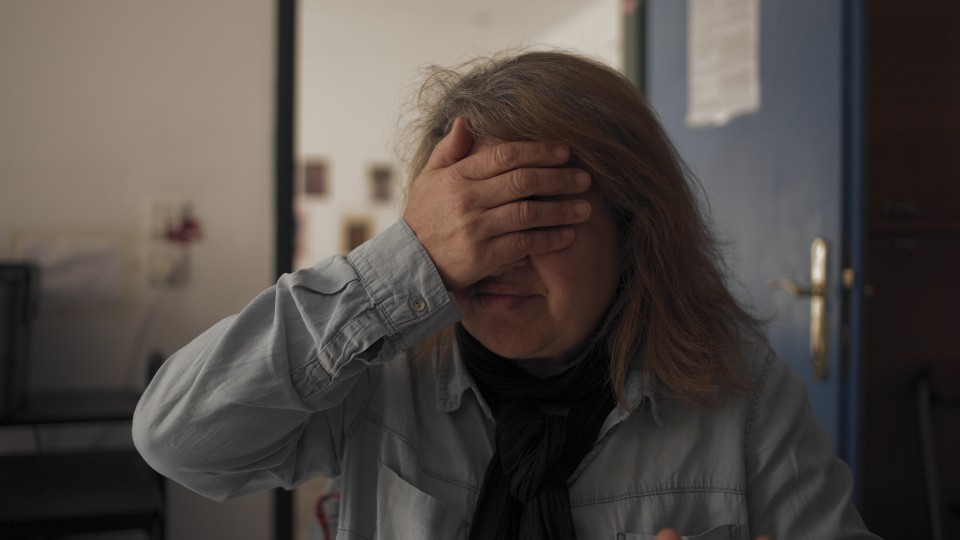

NATHALIE BORGERS: These people, who have suffered so much, lost loved ones and survived years of prison and torture, have also seen themselves

lumped together with all opposition movements and labeled as terrorists. The people who campaigned for democratic causes back

in the seventies have never been recognized for the positive results of their commitment. On a broader level, the chapter

is not closed when the opponents of the democracy movement are still in power. The fact that so much was taken from them,

simply because they fought for a humanistic ideal that harms nobody, is a huge wound.

SCARS OF A PUTSCH establishes a connection with your last work, The Remains – After the Odyssey, and underlines your deep concern with the importance of memory work. What brings you back to this topic?

NATHALIE BORGERS: I have never consciously seen it like that. But actually, my next work also deals with a topic in the past. I believe that

if the past isn’t processed, it will continue to affect future generations. The more you try to push it away, the stronger

it comes back elsewhere.

What concerns me are people's traumatic experiences and the question of how they deal with them. The Remains – After the Odyssey isn’t essentially about the Assad regime in Syria; it’s about the fate of the refugees who emerge as a direct consequence.

These people are a plaything of politics, they count for absolutely nothing with the political decision-makers, but they have

to live with their plight – and so do the next generations.

Your films contribute to the task of coming to terms with trauma. At a far more fundamental level, though, you give visibility

and existence to events and personal fates. It is a work that combats disappearance.

NATHALIE BORGERS: People who see my films can develop a sense of the experiences of people they don't know. And maybe they know someone like

a person from my film. I have two main aims in my films: that the audience should develop an understanding of other people's

experiences and the context in which they took place, and that the protagonists’ traumatic experiences should not be forgotten.

This is close to my heart, but at the same time, the way I keep returning to a similar basic subject area is very unconscious.

Interview: Karin Schiefer | AUSTRIAN FILMS

January 2025

Translation: Charles Osborne