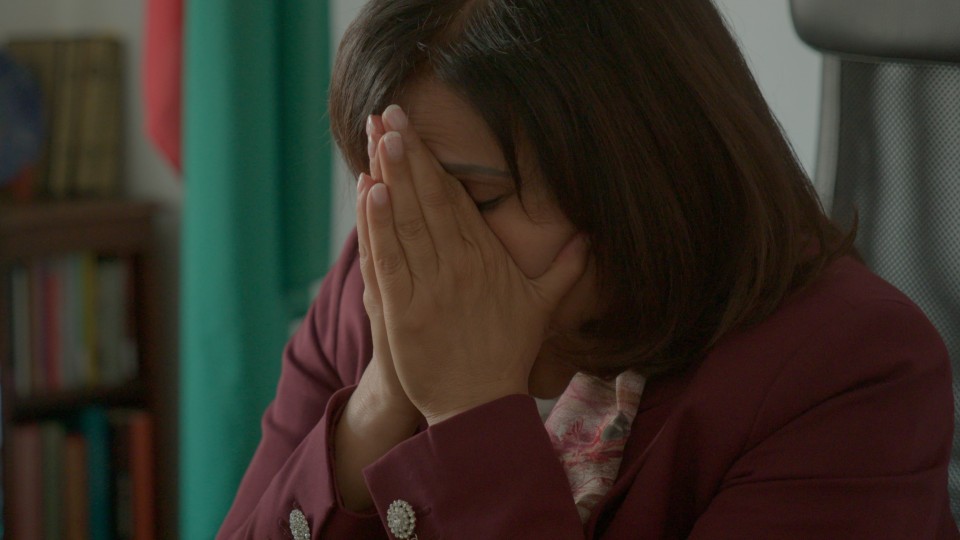

When the Taliban seized power on August 15, 2021, the Afghan Embassy in Vienna had a prestigious location on Vienna's Ringstrasse,

with a dedicated Ambassador in Manizha Bakhtiari. While her function was rendered ambiguous on that day, her critical attitude

towards the new rulers has never wavered. Natalie Halla was impressed by this courageous stance and wanted to create an account

of the weeks of transition. In fact, it turned into a long-term documentary, THE LAST AMBASSADOR, because three and a half years later, her protagonist is still clinging on to her position and using it to appeal to the

world about the shocking situation of women in her country.

You dedicate your documentary THE LAST AMBASSADOR to Manizha Bakhtari, who was appointed Afghan Ambassador to Austria six

months before the Taliban seized power. Who is your protagonist?

NATALIE HALLA: Before Manizha Bakhtari became Ambassador to Austria, she was Ambassador to the Nordic countries, and she had previously

worked as a journalist. She has always been an activist for women's rights and a very committed feminist, employing every

professional position as a platform to advocate the rights of women and girls in Afghanistan. She had actually come to my

attention shortly before the Taliban took power, when she was summoned to the Austrian Ministry of the Interior after drawing

attention in public to the dangers that Afghan refugees face if they are deported. I thought to myself: "brave woman". I next

noticed her when she gave a TV interview after the Taliban seized power; there’s an excerpt from it in the film. I found it

moving, a fine tribute to her personality and courage. I felt a sudden desire to make a film about her, though I also had

the sense that it would probably be impossible. But I contacted her after that interview and asked if I could accompany her

on film until the end of her mandate. Now, almost four years later, she’s still Ambassador. Although she was recalled by the

Taliban, the Taliban regime isn’t internationally recognized. So she just carries on. Neither of us expected that.

How did you succeed in persuading her to take part in the project?

NATALIE HALLA: When I emailed her, she very diplomatically and politely declined – but since she’s a kind and open person, she invited me

to the Embassy to meet her. That visit was my opportunity to persuade her to make the film. I assured her that I would stop

at any point, if that was what she wanted. The human being was always in the foreground for me. I granted her an absolute

veto, right up until completion, even over individual scenes.

What happened in autumn 2021 regarding the status of the Afghan Embassy in Vienna?

NATALIE HALLA: Manizha Bakhtari has been openly critical of the Taliban from the very beginning, so she has really put herself in the firing

line. There was neither money for the Embassy nor any direct contact with the Taliban, and although there was a modest number

of blank passports, they eventually ran out. They had to move out of the prominent premises on Vienna's Ringstrasse because

they couldn’t afford it any longer. From the very start I was actually witnessing a ship sinking: not only the Embassy but

the entire country as well.

In this long-term project, which is focused on one individual, how did you develop the dramaturgy?

NATALIE HALLA: Birgit Foerster, the editor, played a very important role there, which meant that including Jordan Bryon, in the end there

were three of us involved. But Birgit guided the film through the entire editing process, for a year and a half. She managed

to immerse herself in the film, and in the soul of the Ambassador. We went through so many ups and downs together; I've never

made such a difficult film. You can't tell now, because many of the scenes are exactly where they belong, but it wasn’t always

like that. I was creating a portrait of a person whose profession doesn’t generate aesthetic or spectacular images. It’s a

film about a person who talks. How do you make that emotionally moving and maintain interest? I hadn’t realized at the start

how hard that was going to be.

One structuring feature is counting the days. What date is used as the beginning of this count?

NATALIE HALLA: Day zero is the day the Taliban took power: August 15, 2021. I adopted this idea of counting the days from the Ambassador;

ever since that date, girls haven’t been allowed to go to school in Afghanistan. She’s still counting, and it is now 1200

days, which is outrageous. That day zero represents a before and after in Afghan society – it was the day that changed everything.

Manizha Bakhtari speaks English most of the time, but she speaks in Farsi during the passages with her voiceover. Why is that?

NATALIE HALLA: It reflects a desire to get as close as possible to her. When she spoke English, she was automatically more in the role of

Ambassador; in Farsi, she was more Manizha. We were lucky that Jordan Bryan speaks Farsi, which was also an advantage in that

he could conduct the interview with her at a time when the two of us were almost too close. He was able to go into deeper

issues in a different way. Jordan is an Australian filmmaker who lived in Afghanistan for a few years; we got to know him

during the course of the project. He was a perfect addition to our team.

How did you manage to get pictures from Afghanistan?

NATALIE HALLA: As much as I would like to travel to Afghanistan, it wouldn't have made sense. I couldn't have shot any footage for this

film without putting people in danger. So we resorted to every available option, and you can see that there’s a potpourri

of materials. We got mobile phone material from a girl in the Daughters project, providing images of the current emotional situation. There are pictures from social media, a few shots from Getty

images, and we were able to employ high-quality footage shot by Jordan Bryon.

The opening scene is eerie, featuring a line of mannequins in various outfits, hanging from a rail, with their heads wrapped

in plastic bags. What’s the significance of that image?

NATALIE HALLA: It's a shot taken in a normal market in Kabul. It shocked me so much, and at the same time it’s very symbolic. It links up

with the images of the city that you see later in the film, where the eyes and mouths of women on large advertising posters

look as though they’ve been erased. This is in line with the Taliban ideology – the extermination of half of society.

You already mentioned the Daughters program, and Manizha Bakhtiari is one of the founders. What is the idea behind it?

NATALIE HALLA: The Daughters program was created during the period covered by the film as a reaction to the ban on girls' education. It was launched by

Manizha and some diaspora women as a way of taking concrete steps despite feeling powerless when the future of girls there

is in jeopardy. It is one of many initiatives. I’d be very pleased if a side effect of the film would be to make more people

aware of this program and support it.

Was the trip to Tajikistan a way of fulfilling one of your protagonist’s wishes?

NATALIE HALLA: Manizha is a member of the Tajik minority in Afghanistan, and Tajikistan is very close to Afghanistan in cultural terms.

I knew from our conversations that she very much wanted to get to the border with Afghanistan so she could at least touch

the soil. It wasn’t at all sure that we’d actually make it to the border, and how Manizha would react was completely open,

which gave rise to a very moving final scene.

You also indicate what it means for her family that Maniza Bakhtiari is fully committed to a larger political cause. How did

you experience that?

NATALIE HALLA: She’s torn, of course. She’s aware that even though she is fearless, her husband and children are afraid for her. That angle

was very important to me. I’m aware of it in my own life; I also have three children, and that is always in the back of your

mind when you make decisions about your direction in life. Manizha goes her own way, and I wouldn't have made this film if

I were a very anxious mother. This dichotomy, and the situation where you are sacrificing something for a passion, an important

cause, while it can also affect your own family, is familiar to a lot of women in particular.

What is the latest information about access to school education for girls?

NATALIE HALLA: The situation for women in the country is deteriorating from week to week, because more and more decrees are issued. One

of the latest states that windows of rooms facing places where women are present must be bricked up. The separation of the

sexes is being taken to inconceivable lengths. Public schools have been closed, and attending private courses is becoming

increasingly difficult. It’s practically impossible for women to work anymore, and they aren’t treated in hospitals. Women

have to give birth at home, which drives up infant and female mortality. But public opinion around the world turns a blind

eye to all this. Economically, the country is doing badly; hardly surprising since the uneducated country boys in power have

no experience of political leadership. International cooperation and economic relations have been cut. NGOs are also withdrawing

for security reasons.

Has it reached the stage where there are hardly any women still able to work in Afghanistan?

NATALIE HALLA: Almost. At primary school level, girls are taught by women. Attending university is forbidden to women. Opportunities have

been progressively dismantled. At first, the universities were still open to young women, because the Taliban tried to persuade

the international press that their attitude towards women had changed. This first Taliban press conference is part of the

film; Women are a key part of society... But it was all just a lie.

Interview: Karin Schiefer

March 2025

Translation: Charles Osborne