In the mist, contours are unclear; in the borderlands between two countries, it is differences that become blurred. In the

village on the Czech-Austrian border at the centre of THE END OF SILENCE, war and political upheavals have repeatedly created savage rifts through people's living space. Trauma and taboo dictate

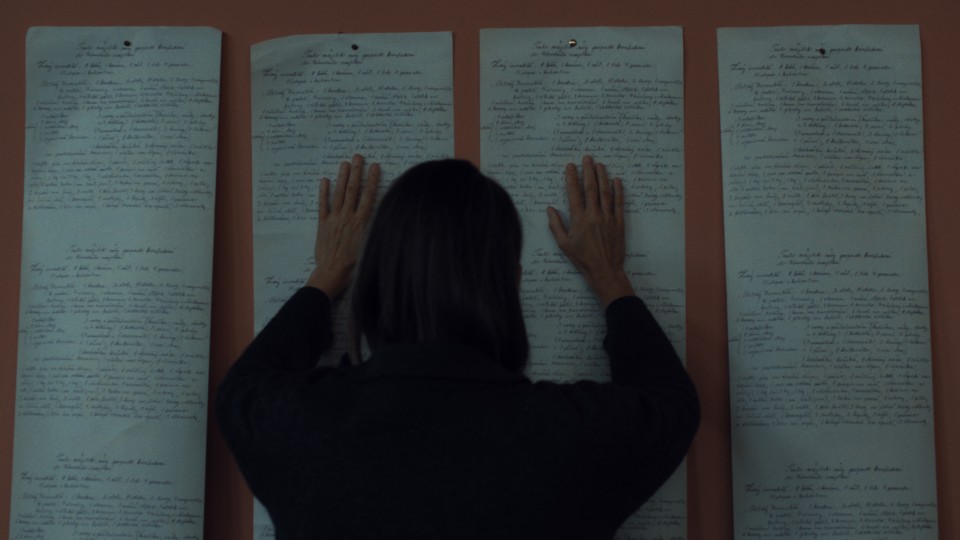

the consequences to this day. Tereza Kotyk has drawn inspiration from the grandchildren of those who lived through World War

II, known in psychology as “mist children”, to expose the violence and lift the ensuing veil of silence that has characterized

the life stories of three generations of women ever since.

The German title, NEBELKIND (literally mist child), has a very poetic element, but it also refers to a concept in psychology.

What does it mean?

TEREZA KOTYK: The term "Nebelkind" is applied to the generation in Germany and Austria born between 1960 and 1975, grandchildren of the

generation who lived through the war. They’re people who have the feeling they don’t know who they are or what they really

want, people with a deep insecurity. They often don’t have children or steady relationships and live in a bubble which offers

them no escape. In many cases they experience nightmares without knowing where they come from. Research is being conducted

into this condition in Germany. It has been recognized how powerfully a trauma from the past can be transmitted to the next

generation by a process of epigenetics – without those individuals having actually experienced it themselves.

THE END OF SILENCE is set on the Czech-Austrian border and touches on an aspect of history, relating to the war and the post-war

period, that is rarely discussed. Which historical events do you refer to?

TEREZA KOTYK: Our protagonist, Hannah, is a war granddaughter who lives in the borderlands between Austria and the Czech Republic, and

this area has experienced multiple border changes. During the course of the war, and in the immediate post-war years, there

were expulsions, expropriations and resettlements.

Were there also autobiographical motives for you?

TEREZA KOTYK: There is an autobiographical aspect, which is that after the fall of the Iron Curtain, my great-grandmother's house was restituted

to my mother. I was very interested in that process: what happens when a house comes back into the family after having deserted

it and belonged to the other side for many years? I was interested in the emotional displacement triggered by that situation,

when the house belongs to you in a certain respect but at the same time doesn’t belong to you.

Hannah, her mother Miriam and her grandmother Viktorie are at about the same age in the decisive moments when we meet them,

when their stories intersect. How would you describe the three characters?

TEREZA KOTYK: The idea was to show the women at about the same age, and that’s virtually how it worked out. I felt it was important to

show Hannah, the mist child, in a bubble for quite a long time. Mist children live their lives with a certain wild component

that makes it hard to connect with them. They have a powerful longing for a family, but they search for alternatives because

they don't trust themselves to maintain a real relationship, which is really beyond them. So they tend to stumble through

a life a little. We show Hannah with the wolves and the whelps. You get the feeling she’s still a sort of puppy herself, despite

her age. We experience Miriam as a mature woman who makes decisions, but in a certain sense they are also displaced. I depict

Miriam as a strong personality, but she is actually the mist that spreads in Hannah and unconsciously triggers trauma. Miriam

belongs to a generation of women who, despite their experience in life, don’t feel themselves; as someone born directly after

the war, she adopted precisely that stance from the war generation of her parents (Hannah's grandparents). Viktorie is someone

who prefers not to feel what's going on. We see at Viktorie in 1945, where she has an inn. She says to herself: "What’s happening

now, I have to get through it." She switches off her own feelings and passes this approach on to Miriam, who consequently

has no access to her own feelings either.

THE END OF SILENCE is set in a region that has changed its national allegiance several times. You make it clear what establishing

a border means for people who can only choose one from a range of bad options: opportunism, remaining as outsiders or leaving.

TEREZA KOTYK: The border runs mainly through a person’s own body. And what is so painful is that it persists over generations. I think

it is important to show the repercussions of establishing borders. Shooting the film provided a fine example: we were filming

right on the border, in a place called Jaroslavice that is now part of the Czech Republic but was once Austrian, as you can

see from certain details. That meant the border is very blurred. Establishing that border also had a huge impact within the

Czech community – especially with regard to the ownership structure after the German-speaking families were expelled. Who

got their hands on what? Nobody talks about it, but you can work it out when you walk through the village. People joined in,

put up with it or left. Maybe some people would have liked to act differently, but in that situation you’re really crushed:

you don't actually want to leave, because it's your home, but you can't stay either. Decisions are forced upon you, feelings

and longings remain within you.

Soldiers are considered the heroes of war. Did you feel it was time to look at all the ways war and political upheavals make

women the ones who bear the brunt of the suffering?

TEREZA KOTYK: What gives me goosebumps is that, because we don't talk about it, it's constantly repeated: I'm thinking of the former Yugoslavia,

the current war in Ukraine, October 7, 2023. What’s the first thing to happen? Expropriation, expulsion, rape. Rape is a form

of dispossession that destroys generations of a family. You can expropriate an entire country in that way. The reason I don't

portray a heroine's journey, and instead allow three generations of women to interact, is that I want to make it clear how

much events from the past affect the following generations. It is primarily the women who pass the effect on, even though

there are also male mist children. That's why I didn't want the film to show soldiers marching or tanks – I didn't want to

put this male power, which is systemic anyway, into a film as well.

One visual leitmotif is the view of the same forest, over and over again. What is the role of nature, essentially, and the

forest in particular?

TEREZA KOTYK: Nature – and the forest in particular – is a space where everything that happens is stored. Atrocities have been committed

in forests during many wars, and that still happens, while people who have been displaced often bury their belongings in the

forest. I wish I could talk to the trees. Trees in particular, since they often stand there for hundreds of years, are therefore

witnesses of both positive and negative events. Thus, the forest in THE END OF SILENCE is on the one hand a dividing element

for the women – it structures the chapters – but also a connecting element, since the forest links the three women; it’s home

to them all.

Both Miriam and Hannah choose lonely professions. Hannah works in a wolf reserve. What prompted you to work with wolves? What

particular attributes do they have?

TEREZA KOTYK: Viktorie’s generation is very social, also in terms of profession. The further we move towards the present, the more these

women find themselves isolated. Hannah, for example, even locks herself into the reserve to watch over the wolves. She prefers

the wolves; they speak more strongly to her. Another displacement activity; her real home is shifted to a different place.

Hannah searches for a home in a wolf family, where the animals are loyal to each other and take care of each other. She doesn’t

make the effort to create her own human family but instead remains in the pack, which also protects her. She doesn't want

to cross the border to her mother's house, the border to the Czech Republic.

How did the casting proceed, considering that it was a bilingual shoot?

TEREZA KOTYK: The shoot was trilingual, in German, Czech and English. The languages in the dialogue were German and Czech. I was very happy

that Jeanne Werner agreed to be involved, because she works a lot in the theatre. I wanted Susanne Michel because I like working

with people who are otherwise not so visible in the film scene. She embodies Victoria in the literal sense. It then proved

difficult to find the right actress for Miriam, in between them. It had to be a Czech actress, because this strangeness had

to be felt in the middle, even though she was the daughter or mother of the other two characters, and because it was the border

area between the two languages. Klára Melíšková, who is very popular in the Czech Republic, read the script and immediately

came on board. Other Czech actors also agreed because they are all too familiar with the problem addressed in the film. It

was very brave of them to take part in this film, knowing that they are touching on a big taboo.

In the montage of the different time levels, some transitions are jump cuts, while others are flowing. What goals did you

set yourself when dealing with the time levels?

TEREZA KOTYK: The big task was to make the characters accessible despite the different levels. Do I jump right in, or do I give the audience

time to find their way into a character? At some point, we were faced with the question of whether we should bring them out

of their inner world. That's why we created the prologue. So we also have the other women in the foreground, and that helps

us get used to the connection immediately. Even though Hannah lives an isolated existence in the reserve, she is much more

influenced by the other two women than we can see. We have succeeded in being in the same place with each woman at about the

same time in their lives, moving in ever-decreasing circles towards the central location. A mist child only achieves release

when brought into confrontation with this generation.

Back to the image of the mist child: How did you plan the camera work with Leena Koppe, trying to reference the idea of mist

via blurring and veiling in the visual language?

TEREZA KOTYK: I immersed myself in the films of Jane Campion and in films where you can feel the unconscious consequences on women's lives.

We were very lucky with our locations, which were so magical from the outset that we were able to combine our ideas with what

the locations themselves had to offer. The cinematographer, Leena Koppe, was very open, and that gave us the opportunity to

capture what is in the air – the mist. We always tried to take with us what we encountered. I think that's what THE END OF

SILENCE is about: Am I free enough to face it? A mist child can never approach anything freely.

Interview: Karin Schiefer

September 2024

Translation: Charles Osborne